© 2010 Rex Jaeschke. All rights reserved.

In the first installment, I introduced the general topic and posed some questions to get you in the "What is Normal" mindset. In this part, I'll deal with writing systems. These days, as most of my travel is international the most obvious deviation from my normal routine is being surrounded by written communication in a foreign language, and sometimes with a writing system quite different from my own. [Should that be "different to my own"? British and American English vary.]

I started writing this article in a hotel in Stockholm, Sweden. [And I proofread it in a hotel in Helsinki, Finland, three months later.] Prior to that time, I had been to Sweden once, for three hours one winter's afternoon in Helsingborg after a short ferry ride from Elsinore, Denmark. I know absolutely no Swedish, and have had very little exposure to Swedish people or culture. [I do have some CDs by ABBA and I'm familiar with the Swedish Chef from The Muppets TV show. So that probably qualifies me to be an armchair expert on Sweden on the talk-show circuit.]

From the moment I stepped off the plane at the airport, I saw Swedish writing all around me. Fortunately, some important signs were in English, but as Swedish is a Germanic language—and I have some basic competency in that—I could also understand or figure out some basics. And the fact that quite a few signs used international symbols for things like toilets, money changing, train station, luggage lockers, and such made it all straight forward (unlike when I arrived in Israel [Hebrew] and Jordan [Arabic] last November).

I've been interested in natural languages for many years, and have made a stab at Spanish, German, and Japanese. And I've picked up some basic vocabulary in a few other languages as well. Then I got into formal computer languages, and that led me to formal grammars. Along the way, I worked on specifications for computing environments to support different linguistic and cultural customs. And some years after I started writing for publication, I even managed to get a decent grasp on my first language, English. So let's just say that I'm an occasionally enthusiastic self-taught amateur linguist.

Introduction

To be literate one must be able to read, write, and comprehend what one has read or written. And in the general understanding, this is extended to include numeracy, the ability to understand numbers and basic arithmetic. So when you hear that a person is illiterate that typically means they lack these capabilities. However, they may well be able to speak and comprehend, and even have an extended vocabulary. In short, they aren't stupid! [Unfortunately, here in the US, we've had more than a few instances of professional athletes graduating from a 4-year university and still being illiterate. "How can that happen", you may well ask.]

Fluency has to do with one's command of a language. I've seen references to the idea that being fluent in a language means knowing the basic grammar and having a vocabulary of 2,000 root words. Over the years, I've done my share of learning word lists in several languages, and each time after having learned 10 new ones, I've felt pretty good, until I realized that that was just the tip of the iceberg. While I may know the words for bird and flower, for example, I'm quickly reminded that doesn't help me distinguish a crow from a sparrow, or a rose from a tulip. As a wag once said, "Those foreigners have different words for everything!"

When I started high school in 1965, only the students in the "A" stream (of which I was one) could take a foreign language, and we had to choose from Latin, Latin, or Latin. Yes my friends, Latin was the only choice, apparently because some Education Department bureaucrats had decided South Australia was most vulnerable to attack from the Romans! And boys like me who didn't care for Latin had to take Agricultural Science instead, while the girls' alternative was Drawing. Speaking of Latin, you may have heard of the famous quote attributed to Julius Caesar, Veni, vidi, vici (I came, I saw, I conquered); well, the modern-day version is Veni, vidi, Visa (I came, I saw, I shopped).

Here in Fairfax County, Virginia, to graduate high school in the public school system students are required to take one foreign language for three years, or two languages each for two years. Most schools offer Spanish, French, and German. The high school my son attended also offered Japanese, Russian, and Latin. And most American Liberal Arts 4-year colleges require students to take two semesters of a foreign language or to show proof of fluency to get an exemption.

In 1986, an excellent TV series called The Story of English was aired here in the US. It showed the evolution and distribution of the language as the British Empire expanded around the world. One aspect that I found most amusing was that in more than a few interviews subtitles were added so viewers had a chance of actually understanding what was being said. They may have been speaking in their normal form of English, but it certainly wasn't mine.

Let's move on now to how the written word is actually written.

Alphabet Soup

Simply stated, an alphabet is a set of letters each of which is represented by a distinct symbol. [For the purpose of sorting words alphabetically, the set of letters can have one or more orders; that is, collating sequences.] As I'm writing this in English, I'll use that language to start my discussion. English has 26 letters, which come in two flavors, lower- and uppercase. [Follow the lowercase link to see why they have these names. In Australia, I learned them as small and capital letters, respectively.] Not all alphabets have more than one case. And not all letters in one case have a corresponding letter in the other case (the lowercase ß in German being one such example). And to make it a bit more interesting there is an artificial third case, title case (or letter case). This comes into play when typesetting headings and titles in publications.

For most people using an alphabet, they think of it as the alphabet, not as an alphabet. However, numerous alphabets are in use. For example, the Greek alphabet has 24 letters and two cases. The Classical Latin alphabet had 23 letters (that from modern English without J, V, and W, and with U written as V) and two cases. [Nowadays, Latin alphabet is used for any alphabet derived directly from Latin, so the English, Swedish, and Spanish alphabets, for example, are Latin alphabets.] The modern Cyrillic alphabet has 33 letters and two cases. [Initially, the EU had two official alphabets, Latin and Greek, and if you look at any Euro paper money, you will see the words "EURO" (Latin) and "ΕΥΡΩ" (Greek) printed on them. However, now that Bulgaria has been admitted, Cyrillic has been added as the third official alphabet.]

In English, each vowel and consonant has a different symbol; however, the Hebrew and Arabic alphabets have letters for consonants only. They use other devices to indicate vowel sounds.

Uppercase letters in English are used sparingly, such as at the start of the first word in a sentence, to start proper names, and to write acronyms. However, in German, every noun is written with a leading uppercase letter.

Some alphabets use what look like multiple letters to make a single letter. For example, Spanish has the letters ch and ll. And yes, they do occur in both cases, and if these letters start the first word of a sentence, only the first in each pair is capitalized. Spanish also has rr, but that is really two r's, not a single letter. In Dutch, ij is sometimes considered a single letter; I've certainly seen it as a separate key on a typewriter keyboard.

In the good old days, once we had mastered printing, we moved on to cursive writing. And we were told of the importance of penmanship. However, for many of us, as we grew older, our cursive needed no encryption to keep its meaning secret. Our handwriting bordered on the illegible. The interesting thing now is that with the proliferation of keyboards and keyboard-like interfaces, all electronic communication uses printed letters. As such, does the teaching of cursive still have a place in modern education?

Western European languages have mostly evolved from the Romance languages (Spanish, Portuguese, French, Italian, and Romanian) or the Germanic languages. As I have a basic grasp of Spanish and German, and a smattering of words in French, I manage to read quite a few signs as I travel through Europe and its former colonies. And having also studied Japanese for a while, I tend not to get bothered by seemingly strange or arbitrary rules. After all, perhaps English is the strange language!

Now what about all those dots, bars, and squiggles that we see written above or below various letters in European alphabets? Take French (please!). It has the same 26 letters as English. However, it adds diacritical marks to aid in pronunciation. These are the acute (´), grave (`), circumflex (ˆ), dieresis (¨), and the cedilla (¸). The main combinations are: à, â, ç, é, è, ê, ë, î, ï, ô, û, ù, ü, and ÿ. The English word facade comes from the French façade; the cedilla clearly tells the reader to pronounce the letter c as an s, but as English has no such marks, that hint has been lost. You simply have to know that is how it's pronounced.

Spanish also uses the acute accent mark on its vowels, as in á, é, í, ó, and ú. Once again, these are not new letters, but marks to tell you where to put the emphasis when pronouncing them. In the absence of these marks, the stress goes on the penultimate syllable. These marks can also be used to give the same-spelled word different meanings. For example, sábana means bed sheet while sabana means savannah. Spanish also uses the dieresis, but only on ü. On the other hand, the word señor (meaning a formal version of mister) is widely known by speakers of other languages; however, ñ is a letter in its own right, not an n with a diacritic. Once again, when it was taken into English, the tilde atop it was lost. However, when English took on the word canyon from the Spanish cañon the letter y was added to retain the original pronunciation.

And what about them there umlauts in German, as in ä, ö, and ü? There is some dispute about whether they are separate letters or simply diacritical marks. In any event, they certainly indicate the pronunciation. My family name is Jaeschke, which when written in German is Jäschke, with the a-umlaut having the e sound in egg. [When I went to register the internet domain name www.Jaeschke.com, a German with the a-umlaut version of the name already owned it, so I went with www.RexJaeschke.com instead. Currently, domain names and email addresses have to be written using the English alphabet, so the German ä gets written as ae.]

Occasionally, in English-language typesetting you will see the dieresis (¨) used with English words. This mark is placed over the second of a pair of adjacent vowels to indicate that those vowels should be pronounced as separate sounds rather than as a diphthong. The most common word having this is naïve. Another one is the word Noël, which means Christmas.

The Norwegians and Danes have 29 letters in their alphabets, with the 26 English ones followed by Æ/æ, Ø/ø, and Å/å. [Two uses of these letters in English publications come to mind: Æsop's Fables and encyclopædia.] However, the Swedes like to be different, so their set of 29 letters ends in Å/å, Ä/ä, and Ö/ö. Finnish looks like Swedish with the W/w missing, but its roots are completely different, so the visual similarity is misleading.

Diacritical marks turn out to be very useful, and I can see why people have difficulty in pronouncing many words in English, which has no equivalent visual pronunciation guide. One letter pattern in English that has numerous sounds is ough. There is ow in bough, uu in through, oo in though, au in thought, u in enough, and o in cough (and probably others).

Regarding pronunciation in English, look at the front of a good dictionary to see the list of pronunciation symbols and their sounds. For example, man is pronounced măn and plane is pronounced plān. (The ˘ is a breve and the ˉ is a macron.) There is a whole phonetic alphabet used to describe how letters in other alphabets are pronounced.

Even the sounds of the same letter in the same language can vary from one country to the next. The classic example in English is the letter z, which in the US is pronounced zee while the rest of the world says zed. Of course, with the American version of Sesame Street being exported around the world, that is changing. [By the way, Big Bird is not always yellow. For example, in The Netherlands, he is blue.] Also, the way in which small children are taught their letter values varies between countries. For example, I first learned the short sounds a, b, c, etc. rather than the long names aye, bee, cee, and so on. That is, "the a and the t make at in bat"; not the "aye and the bee make at in bat", which would obviously be quite unhelpful.

Each time I travel to a country that uses an alphabet that is somewhat new to me, I look at a local computer keyboard. At a glance, everything is the same, but on closer inspection, quite a lot is different. As many European keyboards have more than 26 letters and/or keys for diacritical marks, the layout is different and some keys serve more than two purposes. The key sequence I have the most trouble finding and using is that to generate the @ symbol when sending email. And what's that ¤ key for?

At one time, I studied a world atlas in Greek for several hours trying to see what I could figure out about that language. Having taken math and physics classes for some years, I knew most of the Greek letters, but still it was a challenge. Legend has it that Saint Cyril—for whom the Cyrillic alphabet was named—and his brother developed that alphabet from Greek and took it into Bulgaria from where it spread through the eastern Slavic countries on up to Russia. So if you look at the history of those areas you can see where certain influences were made, by the alphabets used in those areas. One unusual example of this is the Serbo-Croatian language. The eastern practitioners wrote it using the Cyrillic alphabet while the western ones wrote it using a Latin alphabet. As a result, you have two groups of people speaking the same language, but neither can read it in the other's written form.

I freely admit to having had almost no interest in history during my school years. [After all, as someone once said, "History is nothing but one damned thing after another."] However, having traveled to some of the places I learned about (the Tower of London, Runnymede, and the Waterloo Battlefield, for example) I started to relate to more and more of it. And now I actually like the subject, and I see its influence on language evolution and distribution.

One thing about other languages that can be confusing is their use of a letter that you have in your own language, but with the two having completely different sounds. One example is the Russian letter C, which is pronounced like the English S (except on Wednesdays between 10 and 11 am, and in leap years). And to make it interesting, the Russian P is like the English R. If you look in photos or films covering the Cold War, the Soviet missiles and space rockets always have the letters CCCP painted on the side. These stand for "Союз Советских Социалистических Республик", which—as I'm sure you all know—in English means, "Soyuz Sovyetskikh Sotsialisticheskikh Respublik". Now "Soyuz" is Russian for "Union", so CCCP in Russian became "Union of Soviet Socialist Republics" (USSR) in English. [Speaking of the Cold War, there is a story about how the US spent $1 million to develop a ballpoint pen that would write in space. The Soviets simply took a pencil!]

Putting the Em·PHA·sis on the Correct Syl·LA·ble

In Part 1, I wrote, "… my Japanese friend Misato would say that not only doesn't she have any lowercase letters—poor Misa—she doesn't have any letters at all or even an alphabet!" So what does she have? As well as Kanji (which we'll discuss later) she has two syllabaries—hiragana and katakana—which together, are referred to as kana.

Where an alphabet has symbols for letters, a syllabary has symbols for syllables. Typically, a syllabary symbol has a vowel sound proceeded by an optional consonant. Some examples in Japanese are ah, kah, sah, go, zo, do, kyu, shu, and ryu. [Note that Tokyo really has only two syllables, to·kyo, not the three that Westerners insist on using, to·ki·yo.] Hiragana and katakana each have 100+ symbols with almost complete overlap. And just about any word can be written in either. Having two systems seems redundant to me, and students of Japanese must learn them both. Loan words from foreign languages are always written in katakana. Hiragana is used to write particles, a curious language element that does not exist in English.

Speaking of loan words, Japanese words all end in a vowel sound or n. So loan words have to fit this model and the syllabic pattern. For example, hotel becomes ho·te·ru, taxi becomes ta·ku·shi, and cheese become chi·zu. [While bread is also an imported idea, it came via the Portuguese, so it finished up as pan, which not only fits the Japanese model, but also comes from the Latin panis.] Rather than invent new words whose meaning is equivalent to foreign words, Japanese takes them literally with slight tweaks to "make them fit". My favorite is a·i·su·ku·ri·mu, icecream. Although these extra vowels allow the words to fit the spelling model when written in Romaji, they are unvoiced, so when spoken, the words sound very much like their English counterparts.

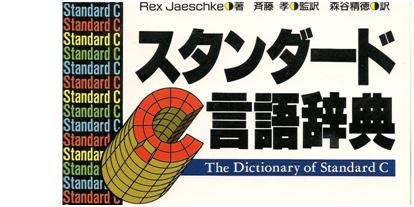

More than 10 years ago, one of my textbooks was translated to Japanese. As my first and last names were of foreign origin, they had to be written in katakana. However, there is no direct way to do that without adding some extra vowels to fit the required syllabic pattern. Here is the cover of that book:

[The same book was also translated to Russian, in which case, my name was written as Рекс Жешке.]

When one starts learning a language, one is told to learn to read and write as well as to speak and listen. In general, that makes sense, but when I started looking at Japanese, the idea of learning 200 kana seemed way too much work. [And that's without learning any of the thousands of Kanji characters!]

Other languages use a syllabary, but the Japanese ones are the most widely used.

Early versions of telex and telegram services were limited to as few as 32 symbols, which for most westerners was sufficient for a single-case version of their alphabets. So, did the Japanese have access to these services?

A Picture is Worth a Thousand Words (Or is it?)

It turns out that alphabets and syllabaries are latecomers in the written language stakes. At the beginning of the written word, we had pictograms, which used symbols that resembled the physical object for which they stood. [Even today, the Chinese and Japanese symbol for entrance is a mouth.] Of course, we have since invented many words that have no obvious physical representation, although pain might be symbolized by a picture of a dentist! Ideograms were also developed and they are symbols representing an idea or concept.

The best known of these kinds of writing systems are the hieroglyphics from Ancient Egypt and the characters used in Chinese, and which were adapted by Japanese (Kanji).

When I was dabbling in Japanese, I did try to learn the Kanji for basic numbers, and I had some success. So even though I could tell how much I was paying when buying from street food stalls, I still had no idea what I was buying. And to make it interesting, many vendors used a combination of Arabic and Japanese digits. For example, 100 would be written with a Kanji 1 followed by two Arabic zeros.

Although I've asked numerous native speakers how they know how to pronounce what I affectionately call "chicken scratchings", I am still none the wiser. In fact, I think they simply have to remember each character. As to how they look up words in a dictionary is a complete mystery to me. And to make it a wee bit challenging, ideogram-based languages seem to have no concept of inter-word spacing, little or no punctuation, and no upper- or lowercase.

To survive in present-day Japan, a student must master the hiragana and katakana syllabaries, have a good grasp of the Kanji ideograms (some with multiple meanings or readings), and then be able to at least read and understand a good deal of English. Many advertising billboards and TV commercials use all four writing systems together! And as for how one enters these kinds of characters on a keyboard simply is fascinating.

Writing Direction

If you are old enough to remember typewriters, you'll recall that large arm on the right that you had to push to the left to return the carriage to the left side and down to start a new line. Of course, with computers this has come to be known as—surprise—a carriage return.

Standards for computer programming languages support the concept of one or more characters that cause a display cursor or printer to advance to the first position of the next line. Of course, for Westerners, that means, "go back to the left side and down". That is, their writing systems are written left-to-right, top-to-bottom. I have no idea why those languages are written that way, but I know of no superior property it provides, so it is no surprise that some writing systems (such as Hebrew and Arabic) go right-to-left, top-to-bottom, and others (such as Chinese and Japanese) go top-to-bottom, right-to-left. I am not aware of any that go bottom-to-top, although that could be perfectly normal, right?

Most writers of Western languages are right-handed, which allows them to read easily what they have written as they write. Not so for lefties, like my son. In many cases, this forces left-handers to hold the pen at a very strange angle. [Speaking of lefties, back in the good old days (the Middle Ages) many people believed that those who wrote with their left hand were possessed by the Devil, and so they were considered evil. The word sinister comes from the Latin word of the same name, and means left-handed. Dextrous comes from the Latin dexteritas, from dexter, which means on the right.]

A few years ago, I made my first visit to the new British Library in London where I discovered its treasure room. [Among other things, it contains the first folio of Shakespeare's complete works, some very ornate Korans, and the lyrics of a well-known Beatle's song scribbled on an airline napkin. I highly recommend a visit if you have the opportunity.] Off in one corner was a room with computer terminals that provided access to a digitized version of one of Leonardo da Vinci's notebooks. Now Leonardo (or "Yo Leo", as his close friends addressed him) was never accused of being normal. In this notebook, he wrote left-handed, from right to left, and back to front. That is, you need to look at a mirror image of the writing to see it in its "normal" perspective.

Conclusion

We've barely scratched the surface of this topic. For example, we haven't talked about sorting order in word lists, punctuation, grammar, or even the spoken word, which is a completely new topic of its own. But, of course, we have to leave something for future installments.

I'll leave you with the following anecdote from my travels in South East Asia in July 1979. I was in Kuala Lumpur, the capital of Malaysia, and Superman: The Movie, starring Christopher Reeve, had just been released there. The Malaysians loved movies and the ticket price was cheap, so each showing was packed. However, Malaysia has four official languages: Bahasia Malay, Chinese, Indian, and English. Although the soundtrack was in English, that was not the first language of most patrons, so they read one of the three sets of subtitles that covered the bottom half of the screen. At the same time, they were talking loudly amongst themselves making it difficult for those few of us trying to listen. For them that was normal.